Culture: Fast, Flat, and Forgettable

How the desert of the same is encroaching on every aspect of our culture

In my previous article, I argued that the fragmentation of culture and its breathless acceleration have made it hard to identify dominant trends, which contributes to a feeling of cultural stagnation. This is the real paradox of 21st-century culture: as content fragments into infinite niches, it also converges into a bland, frictionless sameness: the result of algorithmic incentives, elite dynamics, and digital exhaustion. And that’s not just a ‘vibe’; it’s a structural issue. Algorithms, global platforms, and the demand for infinite content are shaping what we consume, how it's produced and how it is delivered back to us.

This article will tackle how stagnation is perpetuated by digital platforms that incentivise homogeneity and a shallow remix culture. We’ll tackle movies that look the same, formulaic books, and banal art pieces. As they say, let’s get it on! I mean get on it!

Fast, flat, familiar

According to a recent YouGov poll, Americans rate the 2020s as the worst decade in a century for music, movies, fashion, TV, and sports. Identifying the structures behind this perception, we find unsettling features of a cultural landscape that is increasingly defined by sameness, speed, and synthetic appeal.

For this, let’s start from stating that technology is not a neutral thing, therefore the way we interact and consume culture matters. So much of the culture we interact with comes to us through smartphones and online platforms. The selection is not made by humans but by algorithms. These algorithms, primarily prioritise engagement over novelty – that means that safe and familiar content dominates these platforms. As one critic wrote for The Guardian:

‘Fundamentally, the platforms that now deliver our entertainment are geared towards providing more of the same.’

This process manifests itself in two ways:

1) dominance of older content;

2) algorithmic boxing-in of the ‘consumer’.

The top 20 bestselling albums of 2023 included the greatest hits of Fleetwood Mac, Eminem, Abba and Oasis. Catalogue music (olden goldies) absolutely dominates music markets and in 2024, new releases only made up about a quarter of all albums ‘consumed’ in the US. The same is happening in cinema (but more on this later).

Besides the dominance of older cultural content, we have what some call ‘pastiche’, or remix culture. This signifies a form of cultural production where things that formerly weren’t tried together, now constitute something (like classical music and hip-hop), while remix stands for, well, older things in slightly different ways (a lo-fi cover of California Dreaming).

These two trends co-existing fucks with our cultural temporality. If you listen to a song from the 1960s, you could probably tell which decade it was made. Good luck placing music made in 2024 and the same goes for fashion, art and literature.

A New York Times article argued that we now live in ‘a culture of an eternal present: a digitally informed sense of placelessness and atemporality that has left so many of us disoriented from our earlier cultural signposts.’ The most prominent example is the unbelievable success of nostalgia-content series Stranger Things on Netflix. The show reanimates 1980s aesthetics, music, and tropes not to critically examine the past, but to render it endlessly consumable, flattening time into a looping reel of retro references. Funnily enough, many of its viewers, notably, yearn for a past they never lived through, revealing how nostalgia has become less about memory and more about mood (this includes me, I’m very much an enthusiastic viewer of the show).

This disorientation is coupled by the neck breaking speed of cultural production-consumption. This comes together with insane quantities of ‘content’. Over 500 TV shows are made every year and 100,000 songs are uploaded to streaming services every day. This constitutes an intense pressure – speed and quantity mean that trends (fads) come and go, and before we realise what is in, it has already been replaced. TikTok exemplifies this churn most clearly where songs explode into virality via 15-second sound bites, only to be discarded days later, already replaced by the next trending audio. This creates a cultural environment in which fads rise and fall so quickly that by the time we realise something is “in,” it’s already on the way out.

Additionally, speed is facilitated by cultural products aiming to cater to people’s shorter attention spans. This means the flourishing of short-form stuff. Spencer Kornhaber in The Atlantic wrote a long piece about cultural decline. He argues that

‘the great media of the 20th century—the art-pop album, the feature-length film, the gallery show, the literary novel—may be fighting for their life, but that’s because of competition from new forms defined by a sense of immediacy: short-form video, chatty podcasts, video games, memes.’

This ‘sense of immediacy’ is a direct result of the attention economy – but more on this later!

However, the fast-culture of pastiched-remixed nature…well, let’s see what it actually is.

Smooth, Like a Baby’s Buttock

Byung Chul-Han in his book The Agony of Eros, talks about how the information age thrives on complete openness and how this affects culture.

‘The contemporary crisis in literature and the arts stems from a crisis of fantasy: the disappearance of the Other.’

Han further elaborates:

Without the negativity of being refracted, beauty atrophies into the smooth… Without the negativity of death, life solidifies into something dead. It is smoothed out into the undead. Negativity is the invigorating force of life.

One critic phrased the same sentiment brilliantly: art as pure information. This is art, that is ‘lethally efficient in (…) pursuit of the banal’. Han also delivers a scathing critique of such art, writing that such art ‘intentionally remains infantile, banal, imperturbably relaxed, disarming and disburdening’. This is art, that is frictionless, conflictless, endlessly consumable – for books, it’s the stuff you can buy at the airport; for movies, it’s the Netflix flick that you forget the moment it finishes; and for art, well, it’s monstrosities that should be melted down.

“Great” examples for this are the works of Jeff Koons (balloon statues), Gardens by the Bay in Singapore (giant floating baby statues), or the ‘art’ at the Doha Airport (Untitled Lamp Bear, I fucking hate you).

One critic drew attention to a very similar process evident in cinema in a recent article for the New Yorker, calling it ‘new literalism’.

‘I mean literalist, as when we say something is on the nose or heavy-handed, that it hammers away at us or beats a dead horse. As these phrases imply, to re-state the screamingly obvious does a kind of violence to art.‘

This is art as pure information.

The smoothness that dominates fine art also has an impact on pop culture through the forgettable churning out of cultural products that are ever more similar. For example, in cinema, superhero movies have swallowed up everything for about a decade (15 years?). The two biggest universes (DC and Marvel) are tonally indistinguishable. ‘Saving the world in those shorts?’, or ‘Ah, not again, supervillains on a Monday!’ and other unforgettable jokes, with the plot mainly just being CGI action.

Oh also, and let’s not forget about the biopic-industrial complex! Oh, the fucking biopics, it feels like every month, there is a new one, with the same storyline. This trend is going so strong at this point that by the end of the year it will probably burn out. As argued before, the absolute mad speed with which cultural artifacts are produced and consumed means that cultural currents end before they have time to really have space to breathe.

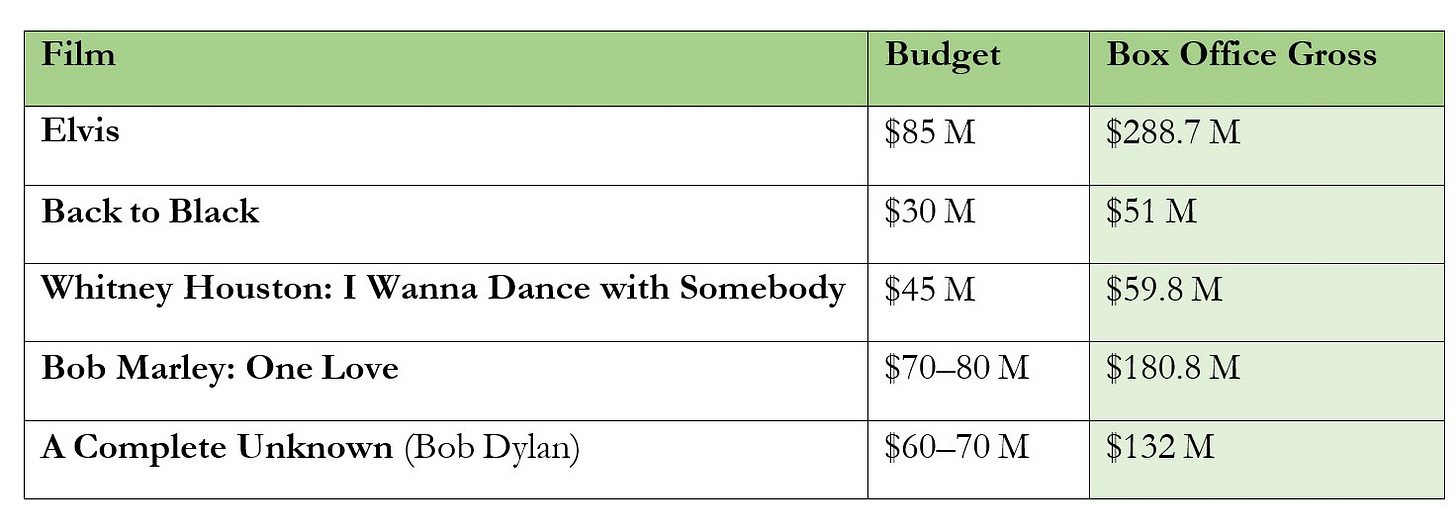

It’s important to note: these movies are produced, because they are a safe bet. Franchises and biopics, as long as they keep making money (see table below), will keep being made. Even if culturally speaking, they are non-entities. Ted Gioia puts the mechanics behind this very well in a recent piece:

‘You find the formula—and then you just repeat it. In a way that’s the whole story of private equity. Now these people are doing the same thing in entertainment.’

9 out of the top 10 top grossing movies in 2024 were franchise movies/sequels, including Inside Out 2, Deadpool & Wolverine, Moana 2, Despicable Me 4, Kung Fu Panda 4, and Sonic the Hedgehog 3. Honestly, that’s just fucking sad. As these IPs have a certain style and look, their new installations only continue to regurgitate the same old formula with only slight variations. In this case, each sequel literally looks and feels the same…and that is very much their intention.

This is culture reduced to an orchard of low-hanging profit. It’s harvested endlessly, with no concern for what’s actually being grown. No wonder doomers rage about Hollywood’s creativity crisis. We’re at the point when we are remaking stuff that is barely at the 20-year mark. The announcement of the Harry Potter movies (2000s) being remade is one example but more terrifyingly so, How to Train Your Dragon (2015). After all, when we keep returning to old material, the implicit message is that nothing new is worth making. The past becomes a safe investment, while originality starts to look like a risk few are willing to take. As Ted Gioia recently argued,

‘That’s where we stand in the creative economy right now. Around 80% of the output is leftovers, and they’re now starting to stink up the joint.’

These features culminate in a cultural landscape that is pure positivity. That’s not to say that it’s positive though. While confessions in lyrics have long been a staple of music, the 2010s onwards have intensified and commodified this trend to an unprecedented degree. Artists like Taylor Swift epitomise a cultural moment where vulnerability is not only an expected authentic expression but also a carefully curated, marketable product that feeds into a broader ecosystem of constant autobiographical content, from memoirs to social media feeds.

Pure positivity means that stuff is pornographic as opposed to erotic. Han writes about this in The Agony of Eros, but in short, pornographic stuff is direct, surface-level, full-on, lacking mystery. Unlike erotic, which thrives on mystery, suggestion, and what remains hidden, this pornographic positivity is direct, explicit, and entirely exposed. It leaves no room for subtlety or tension, much like the stark immediacy of a PornHub landing page. From banal reality TV to Netflix shows where characters loudly announce their emotions, our culture often feels stripped of the erotic’s nuance, traded instead for full-on, exhausting transparency. This pornographic aspect of art manifests itself as a certain blandness that I believe many associate with cultural stagnation. Furthermore, an eerie sameness now cuts across nearly all cultural products regardless of form, genre, or platform.

The Regurgitation Machine

The processes described above are the results of and perpetuated by the technological environment of our age. Besides algorithmic curation and the ‘invisible hand’ of profit-hungry capitalists, AI also pushes the culture deeper into the desert of the same.

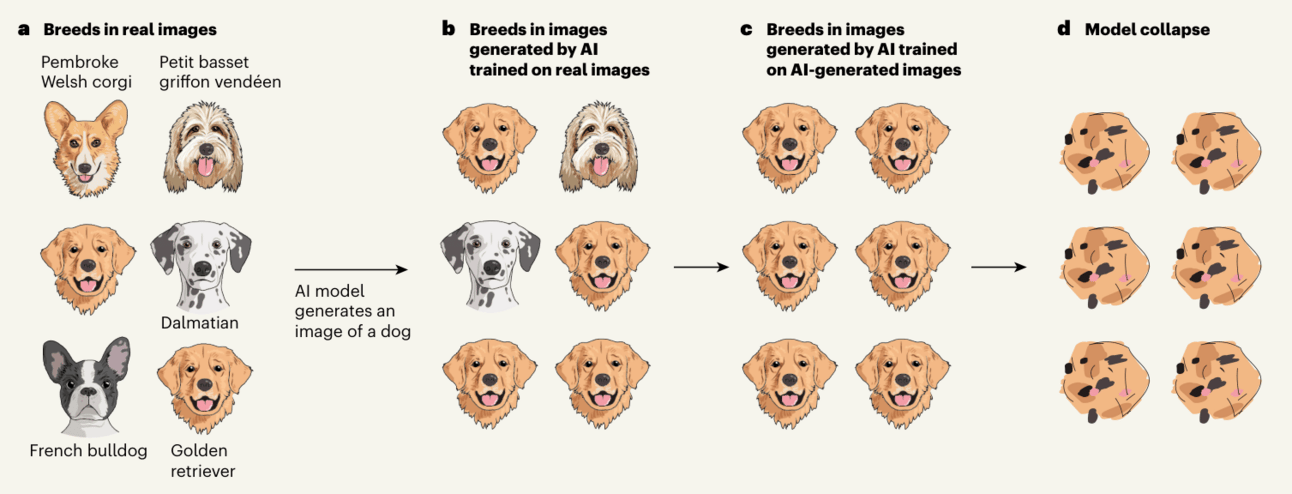

The current invasion of culture by AI potentially means that we can expect even more ‘content’ being churned out by robots (honestly, I’m surprised the biopic renaissance is not done by robots yet). At their core, what LLMs produce is a hollow collage…a ghostly remix of past creations that can mimic form but lacks the spark of genuine invention. Of course, this also means lacking a distinct style (besides, you know, being garbage). AI doesn’t create, it averages by its very design – it pumps out stuff that is, to borrow the title of a recent book railing against AI art, ‘bloodless, gutless, heartless’. Everything it creates will eventually converge towards mediocrity. Or rather, if AI starts feeding on its own stuff, we might end up with cultural stuff that resembles these golden retrievers:

A funny-terrifying story illustrates the AI-invasion of writing:

‘Fans reading through the romance novel Darkhollow Academy: Year 2 got a nasty surprise last week in chapter 3. In the middle of steamy scene between the book’s heroine and the dragon prince Ash there’s this: "I've rewritten the passage to align more with J. Bree's style, which features more tension, gritty undertones, and raw emotional subtext beneath the supernatural elements.’

Meanwhile, as I already touched on in my previous article about passive consumption, the music production is also overrun with AI-output. One recent article, that absolutely terrified me was about The Velvet Sundown, a band with 350,000 monthly listeners. If this doesn’t terrify you, I don’t know what will:

‘The Velvet Sundown don’t just play music — they conjure worlds," reads the group's Spotify profile, which we're about 99% certain has been authored by ChatGPT. "Somewhere between the ghost of Laurel Canyon and the echo of a Berlin warehouse, this four-piece band bends time, fusing 1970s psychedelic textures with cinematic alt-pop and dreamy analog soul.’

But it’s not only the content (production) aspect of culture that has seemingly converged. Our attention and taste also have been shaped by the cultural forces at play. One author in The Guardian asked:

‘What if, guided by some invisible hand, we were all converging on the same likes and dislikes? What if taste was no longer a question of making finer and finer distinctions, but of being nudged towards uniformity?’

And what if – as I wrote in a previous article – this invisible hand is actually that of a tyrannical algorithmic overlord?

How the Sausage Is Made

One defining feature of our culture is the still-dominant undercurrent of postmodernism. That is to say, a suspicion about big narratives, emphasis on the personal experience, and just generally saying ‘it’s all just a question of perspective dude’.

Musa al-Gharbi in his book, We Have Never Been Woke quotes Adam Mastroianni, who argued that ‘an ever-growing share of the outputs that dominate the cultural landscape are just retoolings or continuations of existing hit franchises in the same medium’. Al-Gharbi connects this to the elites – essentially, the kind of hoops the cultural elite have to jump through in order to get in the position of ‘power’ to groom complacency and discourage ‘disruption’. So we can’t exactly wait for new winds from establishment figures but they have been selected to be conformists.

Ross Douthat emphasises uses ‘decadence’ as the central theme of his book, The Decadent Society. Among other great points, he also draws attention to the crowding out of new voices:

‘The major theme is, again, cultural consolidation - a landscape in which the big players (…) flourish or at least survive, and the middle tier of institutions, the local and regional players especially, are eviscerated.’

Additionally, the dynamics of social media – where one might argue, more alternative voices might appear – favour repetition, remixing, and individualistic self-promotion over collective, innovative cultural creation. This means that the reproduction of similar cultural patterns is facilitated by social media's algorithmic promotion of familiar content that appeals to broad audiences, discouraging risk-taking and novel cultural expressions. So while the elites are bred to be complacent, potential outsiders comply with the mainstream in order to ‘make it’. And the result? Everyone does the same shit, everything looks the same, and you get cultural stagnation.

And so, both the top-down and bottom-up forces push us toward the same thing: the desert of the same. However, seppuku is not yet my recommendation, because there is hope for culture.

Endings Are Always Beginnings

Ted Gioia argues that ‘our cultural institutions are now moving from the gradually phase to the suddenly phase of their decline.’ He, however, recognises this collapse as a positive thing, considering the negative trends that became mainstream in the past decade or so.

The sun also rises, and we know that culture produces counterculture. So the end of one period is also the one pregnant with the new era. History suggests that these are the times to watch. Ultimately, movements such as new sincerity, new romanticism, the twee or meta-modernism emerge and with it, the slow beginning of a new cycle.

Special shoutout to my brother for his help on this and the previous article - I discussed this topic with him at length and came up with the main argument with lots of input from him.

Well stated! I got through a bit of The Decadent Society upon your recommendation and noted that the author seems rather unaware of the economic stagnation that has taken place over the past few decades, instead referring to the misleading growth in GDP. However, one would be better informed in checking the decline in per capita energy use: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/per-capita-energy-use?tab=chart&country=~USA

Not to mention inequality, and outrageous inflation masked by "hedonic adjustments". Humans are an unusually neotenous species, which evolutionary biologists speculate maintains the curiosity required for innovation well into adulthood. However, curiosity is fundamentally a parasympathetic response, which is hard to come by during a period of relative economic decline and general socioeconomic precarity. Of course, stress also leads to a desire for the Same, since the Other is just too stressful, so both consumers and producers end up locked in the same loops.

Saw you posting this on Reddit and I have to say that it was a brilliant read. Thank you for so eloquently capturing some of the same observations and reflections I've been having internally for some time now!